Today we walked a single street and it took us so long, photographing, chatting to folk seeking clarification or information, stopping for lunch, then again later for a cuppa, that the whole day just flew. It was one of those magical days that are so special in their happening that you know that trying to go back and replicate the experience will never work. It never happens the same. So this is one for the memory bank.

The street is Redchurch Street. It is technically in the East End as Brick Lane actually runs vertical to it and that is now the famous Bangladeshi street. We visited Redchurch Street solely because we listened to a podcast by Rick Steves, and one of his travel writer guests when asked by Rick what was the one thing he would recommend someone doing in London, replied: walk Redchurch street. So, we did.

We found it chaotic, colourful, filled with characters, élan, individuality and creativity. Quite different from the usual sterility of most modern urban spaces. Old cheap buildings are being given a new lease of life by street artists, unique traders, start-up tech companies and coffee shops. Ten years ago, many traders told us, you would not turn into the street its reputation was so bad. Today, there is even a Versace store to be visited here.

Though, somehow, it is all quite different from the norm. Business hours are flexible. One shop is open all hours for example, though its door is not. Its sign says it all. Another shop owner must have received a telephone call from her customers as she arrived at the store with a key to open it just as they arrived and animatedly started pulling clothes from the shelves, exploring the stock. Another was a dedicated shoe shop. Odd shoes. Designed in Hackney, and made by a Spanish cobbler in Alicante who has been making shoes since the 19th century, so highly skilled is the message. Another sold men's clothes. The clothes collected were considered 'curated'. As with a rare collection in a museum.

Another occupied an old street corner pub and named it

Labour and Wait after a Longfellow poem we were told, advising that the fruit of hard labour pays off if you have the patience to wait for it. This store sold one-off iconic products, be they old or new. I was delighted to find a measuring cup I have always loved on their shelves. One I had for many decades, then lost, then, only recently found a replica replacement at home. This one is likely a replica too, but someone like me will happily buy it. And that is what this store is all about. Waiting for the right person to turn up. It was packed. People were touching the products, like specialty pieces, enjoying them, recounting their history with the piece.

One shop had windows dressed with blow up clothes: for days when you feel thin, I guess. Another, run by an Antalyan barber from Turkey, is around the corner in Brick Lane and plays on the theme of the Victorian serial killer who operated around these streets. He calls himself

Jack the Clipper. He does his best work with razors. In the neck area. He demonstrated.

We tried

beigels at one shop, touted as the best in London. They are nearly as good as New York's. And lusted after the fresh whitloff and truffles sold in a tiny corner sandwich shop where the chef was making his own massive loaves of bread daily in an large open bakery at the back, cutting them into thick outsized slices for sandwiches, and folk were slathering on their own fillings from giant bowls of possibilities, then sitting around large share tables busily engaged in conversation while trying to get their mouths around their lunch.

Small tech firms, start-ups, advertising agencies and small film companies run their businesses from sofa chairs in vast spaces with computers on communal tables hooked up to power. And occasionally move into a coffee shop for a dose of intensity. Or chat to someone in the street during an inspiration break. One firm sold 'bunker space': here, where you could hire congenial spots around a vast warehouse-type room, furnished with odd chairs or shabby-comfy sofas throughout the space: for an intense meeting or just a quiet period of peace. With a bar in one corner for refreshments.

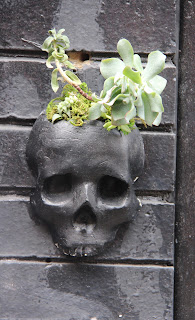

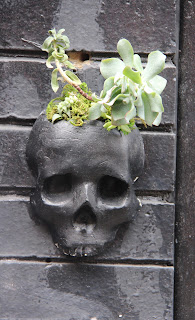

Many of the shops have a small door off to one side of the building leading to apartments above, usually no higher than two floors. These sometimes have masks attached to the wall: many highly and individually coloured; others left simple. 'Protest masks', we were told by a French lady walking with her interpreter. She heard us wondering about them, and through her interpreter offered the case that she believed they started out like Anti-Sarkozy sentiments, protesting nuclear power proliferation by wearing gas masks, and have now become a symbol of protest against many social wrongs. This one wore plants. Maybe the message today is Grow Organic. It may even change tomorrow.

Each of these doors up to apartments were uniquely decorated. We took dozens of photos of them, but these are just a few. The doors match the characters walking the streets, who are as unusual as the shops, and the apartment fronts, ranging from the highly colourful, to the eccentric. We were noticeably the outliers in the street: the oddities. The street signs are in two languages. There is street art everywhere. And sometimes stickers imitate street art.

While street art mimicking life. Here is the face of Charlie Burns, the King of Bacon street, now gone. Charlie's daughter still runs the second hand furniture and paper goods store that Charlie started in an old garage-like building. She told us Charlie was born further up the street in a building long gone and rarely left the area. He made a bare living selling papers that he and his brothers collected and took to the Limehouse Paper Mill for processing. And running boxing championships to keep young East Enders on the straight and narrow, and off the mean streets. For 97 years Charlie barely moved from this area. What little money he made he gave away Helping other people have a go. A true East Ender of the old school. Charlie once owned most of the buildings along his street. Because no one else wanted them. And they were there. Never worth much in Charlie's time.

Now, it is different. Some of the new, fresh, young startups of the new school who have found affordable space here over the last five to ten years are complaining: they are being pushed out. It is all becoming too expensive. Had Charlie lived a wee bit longer he might have seen the fruits of his labour. But, such is life.

|

| Open mostly, closed sometimes, kitandace.com always |

|

| Designed in Hackney, hand crafted in Spain |

|

| A curated collection... |

|

| Labour and wait |

|

| Some old, some new, some iconic, some uniquely designed |

|

| Blow up gear |

|

| Jack the Clipper |

|

| Nearly as good as New York beigels |

|

| Whitloff beautifully arrayed |

|

| Truffles on tap |

|

| Sandwiches made to order |

|

| Bunker space offices for rent with a bar in one corner |

|

| 'Protest Masks' decorated apartment entryways |

|

| Uniquely decorated apartment doors |

|

| This one, unusual and personal |

|

| This one, stylish and impenetrable |

|

| Eccentric and clever |

|

| Colourful street characters come out to converse |

|

| Walking |

|

| Curious |

|

| Busy |

|

| Chatting |

|

| Pondering |

|

| Street signs in two languages |

|

| Street art everywhere |

|

| Humorous |

|

| A family on the move |

|

| Study in black and white |

|

| Entry door art |

|

| Carved squirrel |

|

| Shadowhand |

|

| Cocoon evolving |

|

| Vibrant colour |

|

| Simple line art |

|

| Stickers imitating street art |

|

| Street art mimicking life |